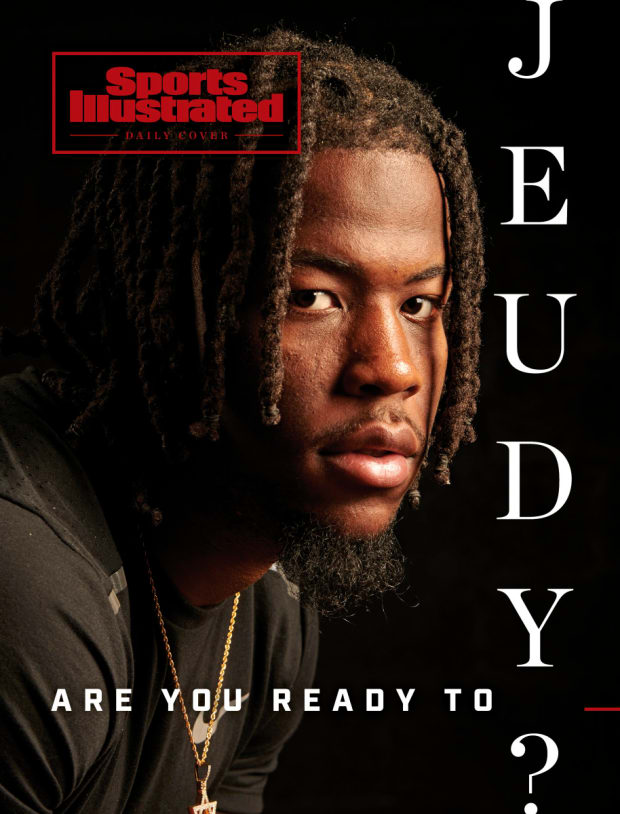

The Alabama product has captured the attention and respect of great receivers young and old. The best wideout in the 2020 draft, from his introduction to football to the real story behind the Star of David he wears.

Back home, his name has become a verb. On fields throughout South Florida’s Broward County, aspiring players of every age have taken to stutter-stepping, dead-legging, spinning, juking and jitterbugging as they imitate their favorite wide receiver. Where earlier generations hollered “You got Mossed!” while embarrassing opposing defensive backs, kids today are all trying to Jeudy.

Jevon Glenn sees the craze up close. As a youth football fixture and coach at Deerfield Beach High, where Jerry Jeudy dropped jaws and broke ankles before heading to Alabama in 2017, Glenn is constantly issuing admonishments for dancing in place during practice instead of running drills. Hey, we don’t have time for you to sit there and be Jeudying. Even so, Glenn admits, the arrival of Jeudy (the verb) has made a positive impact. Who better to learn from than Jeudy (the human) about the art of coming off the line of scrimmage?

“From little league all the way up to my seniors,” Glenn says, “when they work on their releases, they call it Jeudying. He’s the release king.”

Even in a loaded position group that threatens the record for first-round receivers in an NFL draft (six), the 6' 1", 192-pound Jeudy stands alone for his ability to shed coverage—selling fakes better than a back-alley watch dealer, operating with a PhD-level command of the route tree. As expected, replicating this isn’t easy for teens. Adds Glenn, “Most of them fall after they get done Jeudying.”

Countless DBs can relate. Viral footage of their demise is readily available. In one video from a 2016 Florida Gators recruiting camp (with more than 4,200 Twitter likes to date), Jeudy

leaves a cornerback splayed facedown with a nasty comeback-and-go double move. Another, filmed at a group workout with Antonio Brown last summer in Ft. Lauderdale, opens with

Jeudy planting and stopping so abruptly on a 10-yard curl that his defender screeches another three yards downfield before a) realizing what has happened, b) attempting to recover and c) finally falling over. It has almost one million views.

“When he gets separation,” says quarterback Tua Tagovailoa, a projected top-15 pick like Jeudy after both left Alabama following their junior seasons, “if it’s a timing route, I see Jerry break his man off so bad and I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m going to punt the ball to you because you’re so wide open.’”

As Jeudy terrorized SEC secondaries—winning the Biletnikoff Award in 2018, finishing second in program history to Amari Cooper with 26 touchdown catches and becoming only the second Crimson Tide wideout with consecutive 1,000-yard seasons (D.J. Hall, 2006 and ’07)—his legions of admirers swelled far beyond kids. Terrell Owens hit him up for a workout when he visited Tuscaloosa before Jeudy’s sophomore year; they ran routes for more than an hour. After a Bama victory last season Odell Beckham Jr. called to congratulate him on FaceTime.

Then there are his DMs, filled with household handles—Davante Adams, Keenan Allen and Stefon Diggs to name-drop several—replying to clips of his jukes with breathless, emoji-laced praise:

You look good. Real real good ground contact.

Savage!

U f----- liveeeee

“When you look at the tape, he jumps out [of] the screen at you,” Diggs says. “Sky’s the limit for him.” Several of the NFL’s best have even reached out to probe for tips on hand placement or hip movement, curious about Jeudy’s approach to the craft. “I’m trying to get to where you’re at, but you’re hitting me up and looking at me, trying to take something out of my book?” Jeudy says, scrolling through some of these messages on his phone. “That’s crazy.”

Most mock drafts project either Jeudy or Oklahoma’s CeeDee Lamb as the first wideout off the board—not a moment too soon for the pros who have been awaiting Jeudy’s arrival since he dusted that recruit at Florida’s camp. “I was like, ‘Who the f--- is this kid to stop and cut like that?’” says the Patriots’ Mohamed Sanu Sr. “Saw more, saw more, then I went, ‘O.K., he’ll for real be one of the best to do it someday.’”

A lofty prediction, perhaps, considering the 20-year-old Jeudy hasn’t lined up for a single NFL snap. And yet it’s nothing that he hasn’t been obsessively working toward since he was a wide-eyed, dead-legging kid from Broward County, hitching a ride on the floor of a minivan.

* * *

In hindsight, Calvin Davis recognizes the numerous safety regulations that he broke that day. But how was he supposed to say no? Just as the Monarch High coach was loading up his silver Nissan, preparing to take six upperclassmen—including future Alabama and Falcons receiver Calvin Ridley—on a whirlwind recruiting trip to camps at Tennessee, Louisville, Ohio State and other D-1 programs in the summer of 2014, Jeudy, then 15, had come sprinting up Davis’s driveway with nothing but a backpack and a pair of football cleats.

“Can I go?” Jeudy asked.

“There’s no space,” Davis said. “Where are you going to sit?”

“Here,” Jeudy replied, gesturing to the spot between the bucket seats.

And so he did, rumbling across the nation’s highways sans seatbelt, then buckling opponents at each stop. There were separate groups for his age but Jeudy, a rising sophomore, kept quiet and joined his older friends, knowing college coaches would pay closer attention to them. “And when it was my turn, I went out and balled,” Jeudy says.

His recruiting stock boomed from there, culminating in a flood of offers. But Davis enjoys telling this story for another reason: “He sat on the floor. That was when you really knew how great he wanted to be.”

There were many such signs. Jeudy didn’t start playing football until seventh grade in Coral Springs; he was the youngest of three kids for most of his childhood, and his mother, Marie, feared for the safety of her skinny baby boy. “But one day she got tired of me asking,” Jerry says. A switch flipped.

Soon Jeudy was joining Ridley and other neighborhood diehards every weekend, darting through cones at Sabal Pines Park, practicing routes in the thick sands of Pompano Beach. On weeknights he would plow through his homework then tear up the backyard grass with ladder drills until his self-imposed bedtime of 9 p.m. At Deerfield Beach he taxed the JUGS machine so hard that Glenn sent it away for a tuneup.

As important as how much Jeudy worked, though, was how much he watched. “I was a highlight maniac,” he says. Whether he was hanging with friends or eating dinner with family, his face was always buried in some sort of screen, tumbling down rabbit holes of tape. “The only complaint teachers had—all of his work would be done, but he’d be watching YouTube and Hudl,” Glenn says. Shifty, smaller types were his favorites: Reggie Bush, Tavon Austin, viral Pop Warner star Cody Paul … “They were just exciting to watch, how they make people miss,” Jeudy says. “I was like, ‘I want to be that explosive. I want to be that elusive.’ ”

He was a swift study. After only two years of youth football, during which his teams won a single game, Jeudy spent his freshman year hopping between Monarch High School’s JV and varsity squads, contributing at both receiver and defensive back. “One game I scored like three times on three catches,” he recalls. “I’m shaking people, making ‘em miss, getting touchdowns. I’m like, ‘Mmm...I’m pretty good.” It was enough to earn his first letter of interest, from Cincinnati. At first Jeudy was simply thrilled to get some flattering mail, though he didn’t understand why. When Ridley explained that the letter might lead to an offer, Jeudy replied, “What’s an offer?”

Another switch flipped. “In middle school I knew I was going to play football, go to high school and then go find a 9-to-5,” Jeudy says now. “I knew college wasn’t an option. Don’t nobody got no money for no college. So I was like, ‘Damn, I don’t got to pay nothing?’ They were like, ‘Yeah, you’ve just got to keep balling.’ Ever since then, that’s all I was trying to do.” In his mind, making it was a way to provide a better life for his family. Especially Aaliyah.

Years later, Jeudy would raise eyebrows at the NFL combine for wearing a Star of David necklace as a homonymic nod to his nickname, Jeu, even though, as he pointed out during his press availability, he doesn’t practice the religion. (“Don’t mean no disrespect to the Jewish people!” he tweeted later.) What everyone in Indianapolis failed to notice, though, was the girl whose picture occupied the symbol’s center.

Born premature with severe health complications that limited her speech and mobility, his younger sister required around-the-clock care for her entire life. Sometimes, if the night nurse was running late, Jerry would come home from practice, help feed Aaliyah and suction mucus from the breathing tube in her trachea while still wearing his football gear. Or he would just sit by her bedside and nuzzle her nose to nose while her laugh filled the room.

“When I took care of her, I used to think, ‘When I get to the league, I’m finna find these doctors to help her learn how to talk, how to walk, stuff like that,’” Jeudy says. “God had other plans.”

Aaliyah, whom doctors once said wouldn’t live past her third birthday, died in hospice care in nearby Boynton Beach, surrounded by family, on Nov, 25, 2016. She was 7. At that time Jeudy was leading Deerfield Beach—to which he had transferred as a junior—to a 28–21 victory over Atlantic in the Class 8A state quarterfinals, ultimately his next-to-last high school game. Upon learning the news from his older brother, Terry, while walking off the field, he stopped in his tracks and cried. “I love you sis, you in a better place now,” Jeudy tweeted the next morning. “I swear I’m going to make it for you and mommy.”

Now that he is almost there, headlining a receiver class that could challenge the 2014 OBJ/Adams/Mike Evans/Jarvis Landry bonanza as the deepest ever, Jeudy has big plans for Marie. A single mother who left Haiti for the U.S. at 14, knowing next to nothing about American football, she worked tirelessly at various jobs—making parachutes at an Army factory, serving as a nurse at an assisted living facility, selling blankets and jewelry out of her car around South Florida—so there was always food on her children’s plates, even if she went hungry.

“My mom would never want us to see she’s struggling,” Jeudy says. “She’ll do everything in her power not to show that. But no matter what we want, she’ll do what it takes to go get it. That’s the reason I’m doing what I’m doing now.” And the reason why he has already picked out what he’ll buy Marie as the first purchase of his rookie contract: a white Range Rover, her dream ride.

“There’s so much more out there in life you can do, but that’s one of the main goals,” Jeudy says. “Buy my mom a car, buy her a crib, tell her she gotta work no more … that’s going to be one of the best feelings ever. I can feel it coming.”

* * *

Why won’t Jerry speak?

That was the curiosity buzzing through the Crimson Tide’s receivers room in September 2017, a few days before the fourth game of what would become a national championship season. A true freshman, Jeudy had already earned a reputation for being reserved since arriving on campus. “Mysterious,” cornerback Patrick Surtain says. “That’s the word.” Even by those standards, though, this week was different. “Everybody tried to talk to him,” remembers receiver Henry Ruggs, another projected 2020 first-round pick, “but he wouldn’t say nothing at all.”

The truth was that Jeudy had sworn himself to silence in frustration over his limited role in Alabama’s offense, having caught only one pass, for eight yards. “I just said to myself, ‘Don’t say a word. Just outwork everybody,’” he says. “Coach [Nick Saban] came up to me, asked me why I was being so quiet. I was like, ‘Nothing. I’m just working.’” While curious to his teammates, the approach brought immediate results. “He was at a different speed in practice,” Ruggs says. “A speed that we’d never seen before. He was just killing it.” That Saturday at Vanderbilt, Jeudy recorded a season-high three receptions for 68 yards and his first touchdown.

The only five-star wideout in the nation’s top-ranked recruiting class of 2017, according to 247Sports, Jeudy expected to immediately follow in the rapid-fire footsteps of ace Alabama route-runners like Julio Jones and Cooper, whose highlights he had studied for years. And perhaps he would have struggled more with waiting his turn if the person directly ahead in line hadn’t been a close friend who was constantly reminding him to stay ready. “Don’t worry,” Ridley, then a junior, would say. “When I get up out of here, it’s going to be you.”

Jeudy first gravitated to Ridley on that minivan ride, bonding over their shared passion for the receiving craft. When Ridley went off to Tuscaloosa, Jeudy often drove from Coral Springs to visit on the weekends; instead of partying or playing video games, they would head to the practice bubble and lay down ladders. “He taught me a lot,” Jeudy says of Ridley. “How to get open, when to use certain routes, how to never let anything distract you from your goal.”

In 16 games against SEC opponents the past two seasons, Jeudy had 85 catches for 1,350 yards.

In 16 games against SEC opponents the past two seasons, Jeudy had 85 catches for 1,350 yards.

Even so, as the Tide’s passing game funneled almost exclusively through Ridley in 2017—his 63 catches and 967 yards nearly quadrupled the next closest teammate’s numbers—Jeudy had to adapt to playing in his mentor’s shadow. “I’d be in a meeting, and I’d have to deal with Coach Saban on my butt about Jerry’s effort on the run game and his effort on the play without getting the ball,” says Mike Locksley then Alabama’s receivers coach and co-offensive coordinator. “Everybody knew what he was capable of doing as a route-runner. [But] he was probably a little more one-dimensional then.”

This led Locksley to draw up a contract in which Jeudy promised to never give less than max effort, no matter the play call, “and then if he did that, he’d be rewarded,” the coach says. Both parties signed the document, and Locksley hung it in his office, summoning Jeudy and pointing to it whenever the latter’s effort on inside runs waned. Sure enough, once Ridley left for the NFL, Jeudy led the SEC with 14 touchdowns as a sophomore, set a single-season Alabama record with 19.3 yards per catch and became its second Biletnikoff winner after Cooper.

Down in Crimson Tide country, the succession line of star receivers can feel biblical: Julio begat Amari, who begat Calvin, who begat Jerry. ... “When you step on the field, you’re playing for all those guys,” Ridley says. But the phenomenon is relatively recent; until Jones went sixth to Atlanta in 2011, Alabama hadn’t produced a first-round wideout since 1968 (Dennis Homan, Chiefs). Now it can’t stop. This season, though the team failed to reach a fifth straight CFP title game, Jeudy, Ruggs, leading receiver Devonta Smith (1,256 yards) and speedster Jaylen Waddle shined as a four-headed Hydra of no-doubt NFL talent.

So synchronized was the quartet that they freely switched assignments after the huddle broke, whether in pursuit of a primo route—like when Jeudy bested Smith in presnap rock-paper-scissors during a 49–7 win over Southern Miss (though the pass ended up going to Waddle)—or to help a teammate by embracing what they dubbed less desirable “brotherhood routes,” Jeudy says. “Maybe someone didn’t really get that many catches, or he’s having a good game and we can get him another touch. I’ll take the brotherhood route, and you get this.”

As Ridley foretold, Jeudy was the standard-bearer for the 2019 unit. “He’s the leader who doesn’t get noticed,” Ruggs says. The guy who tutored Ruggs in fine-tuning his releases and breaks; who always stayed late after practice to tax another JUGS machine; who would report to the facility on Sunday mornings, the team’s day off, and run routes by himself.

The leader who saved his best act for last. Few would have faulted Jeudy if he’d wanted to safeguard his draft stock by joining Tide linebacker Terrell Lewis and cornerback Trevon Diggs (Stefon’s brother) in sitting out the Citrus Bowl. His regular season wasn’t quite worthy of another Biletnikoff finalist spot (his stats were down in part because of a mere five fourth-quarter catches due to Alabama blowouts), but his name was already stamped all over the Tuscaloosa record books.

Instead, Jeudy suited up, torched the Michigan secondary for an 85-yard touchdown from Mac Jones on the opening snap and earned MVP honors in a 35–16 win. As he had told his sister Diane when she asked whether he would play: “Is that even a question?”

* * *

After declaring for the draft Jeudy moved to Dallas to train at an NFL prospect camp run by Michael Johnson Performance and its eponymous founder, the Olympic sprinting legend. Early on, a group of track athletes, including 100-meter gold medalist Justin Gatlin, swung by the center for a workout. Using a high-speed camera and a program called Dartfish, the MJP team captured footage of Gatlin and compared his kinematics—factors like stride posture and arm alignment—to Jeudy’s. Frame by frame, they were almost identical.

“It tells us that he has the potential to run extremely fast,” MJP director of high performance Bryan McCall says of Jeudy. “That doesn’t mean he’ll be able to run as fast as Justin Gatlin, but he gets to some of the same shapes and forms.”

Want to know how Jerry Jeudys? Start with his posture. Unlike taller, stiffer runners, Jeudy sprints with his upper body bent toward the ground—“It makes a number 7 sign,” McCall says—and spends little time in the air mid-stride. “He has a unique ability to be comfortable in those low positions,” says McCall.

Jeudy might never be a jump ball specialist at 6’1”, but his flexible hips and ankles create change-of-direction ability that helps him gain separation to avoid contested-catch situations. In particular, Jeudy loves shaking press coverage with a “slide release,” where he shuffles outside, sells a fade and waits for the DB to open up before darting underneath. “He’s able to stick one foot in the ground and make a deadly move with no waste of motion,” says MJP receivers coach David Robinson, whose everyday clients include Dez Bryant. “You don’t find that too much.”

“I just know that if I tried that, I would break a bone,” says Oregon coach and former Alabama assistant Mario Cristobal.

Adds Locksley, “He’s got a jellyfish body makeup.”

Jeudy credits yoga for loosening his muscles and his natural pigeon-toed posture for his ability to change direction. “My legs are weird,” Jeudy says, which explains why teammates and trainers alike marvel at how he can plant so hard, so fast, and not shred an ACL. “People [tell me] I got no ligaments in my knee, but I don’t know what y’all be seeing. I’m just out there doing what I do, trying not to get tackled.”

Whether he can shake NFL defenders is one big question facing teams on April 23, the first night of the draft, and the day before Jeudy turns 21. “He has a habit, being open so much, toward the top of his routes, where he can chill and relax,” Robinson says. “Now he’s going to have to really focus on finishing his routes.” The F word surfaced again when Robinson watched Jeudy’s film and noted several “focus drops,” where Jeudy turned upfield but forgot the ball. But these are easily fixable issues for someone as obsessed with details as Jeudy.

A week into his time at MJP he “stunned” McCall by asking for the optimal body angle while running at top speed. (It’s 10 degrees.) He similarly caught Robinson off-guard with one late-night text about an upcoming film session: Coach, don’t forget to bring the wide receiver coverage package tomorrow. “Guys who are high profile, you think they’re prima donnas, don’t really like to work, but he loves the film room,” Robinson says. “The scouts are going to be impressed with his IQ, how well he knows coverages.”

Jeudy isn’t worried about his game translating from the SEC to the NFL. Asked what will be his biggest adjustment entering the pros, he shrugs and says, “I don’t know, I feel like it’s going to be a lot easier [than college]. The only thing I’ve got to focus on is football.”

He is relaxing in a lounge chair at Miami Beach Convention Center, three days before Super Bowl LIV. A gold chain with a glittering silver pendant of his initials and college number—JJ4—dangles outside a colorful dress shirt. The Star of David necklace with Aaliyah’s picture hovers over his heart.

Aside from a brief snack break at 10 a.m.-—two bags of nacho Doritos and a plate of chicken wings; imagine what happens when his nutrition tightens up—it has been a whirlwind morning. On top of a car wash of radio and TV hits, Jeudy has been fielding a steady stream of attention from fellow receivers in town for the big game. On the convention center escalator, Cris Carter tells Jeudy that he’s the best route-running prospect since Cooper. (“Knowing Cris Carter and who he is,” Jeudy says later, “that’s amazing.”) Jerry Rice entertains his questions about how to stay fresh during the grind of an NFL season, and how Rice kept going for 20 seasons. Michael Irvin asks to exchange phone numbers and tells him to reach out.

“Keep doing your thing,” Irvin says.

No matter what happens next, part of Jeudy’s legacy has already been written back home in Broward, less than an hour’s drive away. He remains a constant presence at Deerfield Beach, texting players about keeping their grades up, swinging by practice whenever he’s in town. He has even called Glenn at halftime of games, asked to speak with a struggling receiver in the locker room, and offered a pep talk over the phone. “That’s one of the best coaches in the country,” Glenn says. “We can tell the kids something until we’re blue in the face, but if they hear it from him, it’s golden.”

After all, everyone wants to Jeudy like Jerry—even if no one else truly can.

This story appears in the April 2020 issue of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

Ads Section

We appreciate you for reading our post, but we think it will be better you like our facebook fanpage and also follow us on twitter below.